Intro

Ah, the summer of 2016. Wasn’t it magical?

It was July 6, 2016, when Pokémon Go launched worldwide, turning our 4th-grade dreams into reality. Everyone was outside, hunting Pokémon, spinning PokéStops, and competing in gyms.

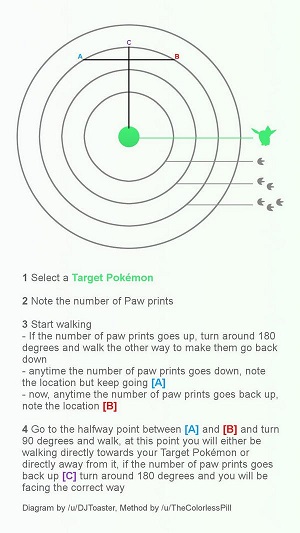

However, living in a rural area meant Pokémon spawns were scarce, and I found myself often fighting the game’s inadequate tracking system rather than with the Pokémon themselves. The system merely used paw marks to indicate a Pokémon’s proximity, making pinpointing their exact location a significant challenge.

The issue lay in the system’s vague indication of distance: “far” (3 paw marks), “near” (2 paw marks), and “very close” (1 paw mark) for each Pokémon. I only saw one viable solution for this predicament - creating a Pokémon scanner!

Little did I know, this endeavor would lead me down a two-week adventure of hacking, reverse engineering, and collaborating with a group of like-minded researchers, all aimed at circumventing Pokémon Go’s anti-cheating mechanisms. This journey was later covered in an Ars Technica article, earning me a special mention in the credits.

Disclaimer: This post is recounted from a 2016 perspective, shortly after the launch of Pokémon Go. The techniques described here have been rendered obsolete by new measures against reverse engineering and mimicking the Pokémon Go protocol. Given these and the time that has passed, I feel safe sharing this tale for its educational and entertainment value.

The Idea - A Pokémon Scanner

The Pokémon Go app shows the 9 closest Pokémon with paw marks indicators. The logic followed that if one could intercept this information from the server, it would be possible to determine Pokémon locations: you’d start from the center location and employ a method of pinpointing the exact location of a Pokémon by intercepting the information received from the server on several carefully-chosen locations, similarly to triangulation.

Furthermore, since this information has to specify the type of Pokémon (enabling showing it in the “Nearby Pokémon” feature), I imagined creating a map that would detail the approximate locations and types of Pokémon around me.

With such a map, it’s just a matter of deciding which Pokémon I want to catch and going directly towards it!

Fueled by enthusiasm (and perhaps needing to rest from running outside all day looking for Pokémon), I focused on the first objective: understanding the app’s communication protocol with its server, and more specifically how it receives Pokémon locations.

Sniffing the Pokémon Go App

Sniffing, just to clarify, is the (totally legitimate) term for capturing both outgoing and incoming network traffic from a device.

In our scenario, the focus was on the data exchanged between the Pokémon Go app and its server. A reasonable assumption is that this communication is secured using the HTTPS protocol.

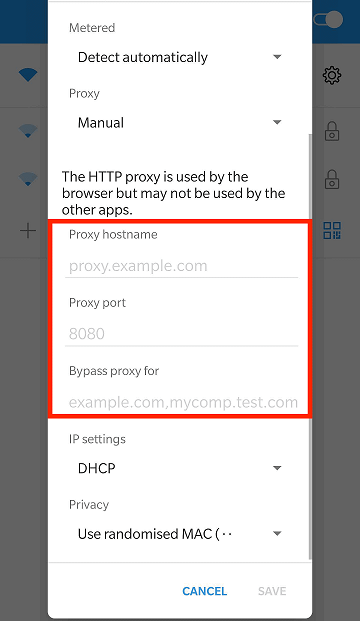

Redirecting the app’s traffic through a proxy server on a computer - which would log all transmitted data - was straightforward. This requires adjusting the smartphone’s Wi-Fi settings to use the computer’s IP address as a proxy.

The challenge, however, was the “secure” aspect of HTTPS.

Underpinning HTTPS, the Transport Layer Security (TLS) is what enables secure client-server communication, effectively blocking eavesdropping on the data exchange. In this case, the eavesdroppers would be us, attempting to intercept the communication between the Pokémon Go app (the client) and its server.

A critical part of TLS is how a client verifies that it is talking with the correct server. This process is done by validating a certificate presented by the server. This certificate is given to the web server owner after they prove ownership of the domain to a Certificate Authority (CA). This certificate, signed by the CA, confirms to clients that they are indeed communicating with the legitimate server.

Since we don’t hold the Pokémon Go server’s certificate, our proxy can’t masquerade as the server of the Pokémon Go app. But, with complete control over the client device (our smartphone), a workaround involves installing a new root CA certificate on the smartphone. (Guides for Fiddler and Burp).

Holding a certificate belonging to a root CA allows our proxy server to sign certificates for any domain, effectively tricking the smartphone into treating it as a legitimate server, thereby facilitating our sniffing attack.

In 2016, setting up a proxy server and installing a new root CA certificate was sufficient for sniffing an app’s communication. Nowadays, apps dealing with sensitive data, like Pokémon Go, have implemented several layers of protection against such attacks. These include:

- Employing SafetyNet or the Integrity API to block rooted or modified devices.

- Implementing certificate pinning to limit which TLS certificates are accepted to a predefined list.

- Introducing native code and obfuscation techniques to complicate any reverse engineering efforts.

- Designing apps to ignore system-wide proxy settings.

Despite these efforts, control over the client device allows for these measures to be circumvented using tools and techniques like Frida for certificate unpinning, Magisk modules for SafetyNet circumvention, and device-native proxies for traffic inspection, alongside a good dash of reverse engineering. A future post will detail my strategies to bypass these anti-reverse engineering protections.

After overcoming the TLS barrier by installing a root CA certificate on my device, I could finally inspect the Pokémon Go app’s traffic.

Analyzing Pokémon Go Traffic

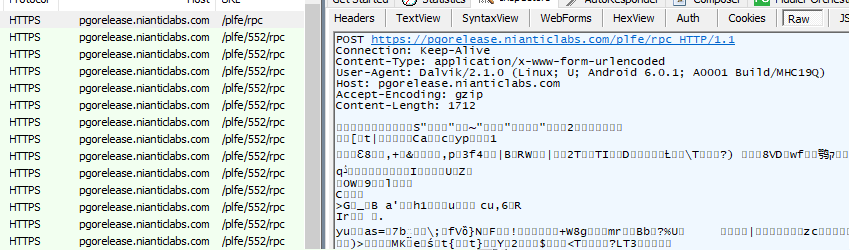

The Pokémon Go app communicates with its server through pgorelease.nianticlabs.com, typically sending requests to the plfe/552/rpc endpoint. The acronym “RPC” usually stands for “remote procedure call”, a term that catches the eye of an avid Android researcher.

Anyway, upon closer look, the POST request contains some oddity: the Content-Type header claims the data within is application/x-www-form-urlencoded, but the actual data is not human-readable, as one would expect.

So what’s going on here? Let’s look at a bit deeper at the data:

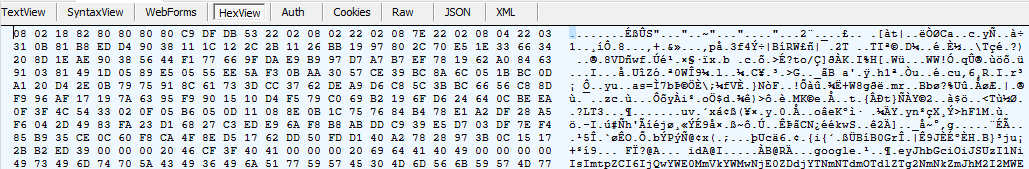

Noticing both the request and response start with the byte 0x08, contain glimpses of readable text and recalling that the company behind Pokémon Go (Niantic Labs) is owned by Google leads us to our first realization: the format used in the client-server communications is protobuf!

Protocol Buffers (or protobuf for short) is a serialization mechanism developed by Google. It simplifies the communication of data structures between separate processes (either virtually or physically), enabling the exchange of complex data structures for communication, regardless of programming language or the protocol of communication.

Protobuf binaries take care of creating the wrappers used for serializing and deserializing the data structures based on the developers’ definition of messages. In the context of server-client communication, developers define “remote procedure call” actions that the server accepts and the client can invoke.

This explains the Google and RPC pieces of the puzzle. The initial byte being 0x08 is a common occurrence in serialized protobuf messages, identifying the first field as an integer (or VARINT, read more here).

Anyhow, as we said, protobuf requires defining a message as a basic structure, representing an object. This structure can include various types of fields, like integers, strings, doubles, and even other messages as sub-objects.

The messages are specified in a .proto file, which can be compiled into several programming languages and imported as a module or library to serialize and deserialize data. A sample message definition might look something like this:

syntax = "proto3";

message SearchRequest {

string query = 1;

int32 page_number = 2;

optional int32 results_per_page = 3;

optional repeated SearchOption search_options = 4;

}

Here, the SearchRequest message contains four fields: the first is a string named query, the second is a 32-bit integer named page_number, and the third is also a 32-bit integer and is named results_per_page. Finally, the fourth field is named search_options and is actually another message called SearchOption which is defined elsewhere.

The use of optional and repeated prefixes accommodates fields that may not always appear and a list of items, respectively.

An actual message using the above definition might look like this:

query: "Lord of the Rings Books",

page_number: 5,

search_options: {

1: "Order"

2: "Ascending"

}

search_options: {

1: "Language"

2: "English"

}

Since we don’t have the definition of the SearchOption message, we don’t know its field’s names and must represent them by their index instead. Notice that you can tell a lot about the SearchOption message even without seeing its definition - a tactic that we will heavily rely on when reverse engineering Pokémon Go’s protocol.

In practice, the message definitions are compiled, so they won’t be present in the same human-readable form in the final binary product (the Pokémon Go app).

To analyze serialized protobuf messages, we need to decipher what each field is used for, effectively reconstructing the original message definitions. There are 2 ways to do that:

-

Tools like pbtk can automate the detection of compiled message definitions within the binary code.

-

Manual black box analysis of messages sent back and forth to identify the message’s fields’ usage.

The second option is definitely more fun, so let’s use it to analyze Pokémon Go’s protocol.

“But wait”, I hear you think. “The messages in your capture are serialized and not in the neat deserialized format you presented. How can you analyze them?” Well, this is where the protoc tool comes in.

The protoc tool is what compiles your .proto files into modules in your favorite programming language.

This tool also supports deserializing protobuf messages without their message definition. By executing $ protoc --decode_raw < serialized_message.bin the tool produces a message as can be seen above, using the field’s number instead of its originally-defined name, while the field’s type is determined by deserializing the message.

Using protoc, let’s look at the deserialized form of the first request exchanged between the Pokémon Go’s app and its server:

$ protoc --decode_raw < request_1.bin

1: 2

3: 1764153216922026362

4 {

1: 106

2 {

1: "\200\200\200\200\200\250\256\201\025"

2: "\000"

3: 0x403f323200000000

4: 0xc0546a8520000000

}

}

4 {

1: 126

}

4 {

1: 4

2 {

1: 1467995033798

}

}

4 {

1: 129

}

4 {

1: 5

2 {

1: "4a2e9bc454dae60e7b74fc93b98868ab4700802e"

}

}

6 {

1: 6

2 {

1: "\363\230\314\364.\200\303\312p\373\271\217\231\233\363qi8\352X\017i\343yP\245,\010PI\364\n\217Z\342L\200\330\317\211iT3\247\'\020I\272\t9\347i\034)\234\305\027\204\303\206\246B\263\333\265\017\340-]2\317\376b\250:\233\201=d\014\272\035\220\365]\265\277k\363\\K\023\307Z\327qHB{\013\251\223\300F\324\314:\332\255\030\327|\3032 Q\301\250\016\225\221\022\213\277q\035\306\341\371\353N\304\325\3449\234\007S\310~\031\205\223\225S2\243\311l\272\014\313\014\347P\344\0373\257\331\205\026\037p\236\202<\241)X\305M\215Rb\222B\320\020\354\261\227\353\2209\013\353\260\221\320\026g\2749\303\327e9`K\202J/\262\355T\316\335\355\t\021#\026\306e\356d\231\263qhzv\326\237\201\305\205,\0168\227\201#\241P\030\207\341@\026s\303\311\222p_\013S\240:\233\037\300\226\1776\320\237c:c\006qe\216X\3139\217\221|\354\366c^gju\214k\202\357\367\037$K\233"

}

}

7: 0x403f323200000000

8: 0xc0546a8520000000

9: 0x403b083120000000

11 {

1: "\'\334W\245C\247\033\200\271r\373\030\371z\357\300\226\357\266\230/r\030\275F\265\232\245L_\000\206PK_\212C\250\331\"\304\244\2053\270\315\270F\207Kk\340\345\224y\332\213\245\364\'\262\241*\261"

2: 1467996809291

3: "\365\255\3318w\333\007Hmb\034@*\2122\272"

}

12: 4590

Inspecting this request, let’s start by listing some immediate insights.

- Number of fields: the presence of field 12 confirms at least 12 defined fields in the message definition.

- Field’s common values: Some fields contain simple integers (1, 3, and 12), others contain integers in a hexadecimal format (7, 8, 9) and the rest are other, sub-messages (4, 6, and 11). One of which (4) appears multiple times so it probably has the

repeatedkeyword. The fields that do not appear (2, 5, and 10) must beoptional. - Significant fields: Field 3 being a long integer appears to be some sort of identifier, maybe of our Pokémon Go account.

- Wrong field type: The type of fields 7, 8, and 9 may be wrongly inferred, and they are actually

double. This happens because some field types are combined together during serialization.

Assuming that all requests from the Pokémon Go app follow the same message format (which is frequent in client-server RPCs), we can use the similarities and differences between requests to understand more about the underlying message. So, let’s parse and review the next 2 requests sent by the Pokémon Go app:

$ protoc --decode_raw < request_2.bin

1: 2

3: 1432598923109335417

4 {

1: 106

2 {

1: "\200\200\200\200\314\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\264\250\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\274\250\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\234\255\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\200\200\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\224\255\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\214\255\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\324\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\344\254\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\254\250\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\354\254\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\204\255\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\374\254\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\364\254\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\244\250\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\334\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\354\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\264\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\344\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\304\253\256\201\025\200\200\200\200\274\253\256\201\025"

2: "\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000\000"

3: 0x403473e0ac000000

4: 0x4058f962d3000000

}

}

4 {

1: 126

}

4 {

1: 4

2 {

1: 1467995033798

}

}

4 {

1: 129

}

4 {

1: 5

2 {

1: "4a2e9bc454dae60e7b74fc93b98868ab4700802e"

}

}

6 {

1: 6

2 {

1: "\363\230\314\364..."

}

}

7: 0x403473e0ac000000

8: 0x4058f962d3000000

9: 0x403b083120000000

11 {

1: "\'\334W\245C\247\033\200\271r\373\030\371z\357\300\226\357\266\230/r\030\275F\265\232\245L_\000\206PK_\212C\250\331\"\304\244\2053\270\315\270F\207Kk\340\345\224y\332\213\245\364\'\262\241*\261"

2: 1467996809291

3: "\365\255\3318w\333\007Hmb\034@*\2122\272"

}

12: 4495

$ protoc --decode_raw < request_3.bin

1: 2

3: 1864153216922026363

4 {

1: 102

2 {

1: 0xa56e05c07131fa3d

2: "1502bffd46b"

3: 0x40459834dd000000

4: 0xc053f993bf000000

}

}

4 {

1: 126

}

4 {

1: 4

2 {

1: 1467995033798

}

}

4 {

1: 129

}

4 {

1: 5

2 {

1: "4a2e9bc454dae60e7b74fc93b98868ab4700802e"

}

}

6 {

1: 6

2 {

1: "\222\024\316\0054\206mb^\210..."

}

}

7: 0x40459834dd000000

8: 0xc053f993bf000000

9: 0x40304147a0000000

11 {

1: "\'\334W\245C\247\033\200\271r\373\030\371z\357\300\226\357\266\230/r\030\275F\265\232\245L_\000\206PK_\212C\250\331\"\304\244\2053\270\315\270F\207Kk\340\345\224y\332\213\245\364\'\262\241*\261"

2: 1467996809291

3: "\365\255\3318w\333\007Hmb\034@*\2122\272"

}

12: 2651

Comparing the values appearing in these requests, we can make the following observations:

- Consistency of fields: field 1 always contains the value

2, and fields 7, 8, 9, and 11 also remain the same throughout the requests. - Field 3: this field is not a global identifier as we thought, however in requests 1 and 3 it only differs by 1. It might be an incremental request identifier instead.

- Authentication: These requests were sent while I was logged into my Pokémon Go account. They do not contain any HTTP authorization headers. We therefore have to assume that some authorization token resides within the request body. A good candidate is field 11 which is a large sub-message that stays consistent across all requests.

- Repeating messages: field 4 suggests a schema where different types of requests are sent together. The small integer in the first sub-field indicates the request type or action being performed and, when it exists, the second field contains the request details.

The last observation is a common occurrence in protobuf when RPCs are used and we’ll exploit it soon.

But first, we proceed to draft a RequestContainer.proto file that combines our understanding of the message structure:

syntax = "proto3";

message RequestContainer {

int32 always_2 = 1;

int64 request_id_maybe = 3;

repeated RepeatedMessage repeated_message = 4;

bytes message_six = 6;

double constant_seven = 7;

double constant_eight = 8;

double constant_nine = 9;

bytes auth_maybe = 11;

int32 small_number = 12;

}

message RepeatedMessage {

int32 request_type_maybe = 1;

optional bytes additional_data_maybe = 2;

}

When analyzing protobuf messages, don’t forget to use Tal’s tips for protobuf analysis™:

- Only add fields that you observed and avoid marking fields as

optionalif they always appeared so far. This approach ensures that if something major changes in the message, your code will crash. - For sub-messages you deem less relevant, utilize the

bytestype. - Use field names that reflect the observed value or inferred functionality. Mark any assumptions you made about the fields’ usage.

We can now compile this .proto file into a Python module by executing $ protoc --python_out=. RequestContainer.proto. This will output a RequestContainer_pb2.py file which we can import and use as a module in a Python script. Let’s write a small script that will load one of the requests and parse it according to the message definition we specified:

from sys import argv

from RequestContainer_pb2 import RequestContainer

def print_request_container(file_name: str):

with open(file_name, "rb") as request:

request_contianer = request.read()

request_container_pb = RequestContainer.FromString(request_contianer)

print(request_container_pb)

def main():

print_request_container(argv[1])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

$ python3 script.py request_1.bin

always_2: 2

request_id_maybe: 1764153216922026362

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 106

additional_data_maybe: "\n\t\200\200\200\200\314\250..."

}

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 126

}

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 4

additional_data_maybe: "\010\306\241\332\312\334*"

}

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 129

}

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 5

additional_data_maybe: "\n(4a2e9bc454dae60e7b74fc93b98868ab4700802e"

}

message_six: "\010\006\022\243\002\n\240\002..."

constant_seven: 31.19607543945312

constant_eight: -81.66437530517578

constant_nine: 27.031999588012695

auth_maybe: "\n@\'\334W\245C\247\200\033...."

small_number: 4590

We can clearly see (well, at least if you meddled with the coordinates of where you live) that we were right in changing the type of fields 7 and 8, and that they probably represent latitude and longitude.

The repeated_message indeed follows the pattern we expected - request aggregation. Under this pattern, the developer creates different types of requests that clients can invoke. The client can aggregate several types of different requests in the same request container according to its needs.

By using this pattern, the server can process requests from clients in a distributed manner by forwarding each request type to its respective handler and then aggregating the responses into a response container which will be sent back to the client. This works well when the types of requests are independent from each other, a common occurrence in online games.

The pattern is facilitated by repeated_message containing the request type in its first field and then the request data (if needed) in its second field. Let’s alter the definition of this sub-message and also add an enum representing all request types we’ve seen so far.

enum RequestType {

type_0 = 0;

type_4 = 4;

type_5 = 5;

type_106 = 106;

type_126 = 126;

type_129 = 129;

}

message RepeatedMessage {

RequestType request_type = 1;

bytes additional_data = 2;

}

The next step is understanding what each request type means. When we do so, we’ll try to identify the specific request types we’re interested in - the ones that contain the Pokémon locations.

Identifying Request Types

Since RepeatedMessage can contain various types of requests, we’ve treated its additional data as bytes, allowing us to dynamically parse the content in our code, based on the type.

Let’s refine our script to do just that, and analyze the requests’ content, black box style:

import subprocess

from sys import argv

from RequestContainer_pb2 import RequestContainer

def analyze_request_container(request_file_name: str):

with open(request_file_name, "rb") as request:

request_container = request.read()

request_container_pb = RequestContainer.FromString(request_container)

for request in request_container_pb.requests:

print(f"Request type: {request.request_type}")

decoded_request_data = subprocess.run(['protoc.exe', '--decode_raw'], input=request.additional_data, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE).stdout

print(f"Request data: {decoded_request_data.decode('utf-8')}")

print("-"*20)

def main():

analyze_request_container(argv[1])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

$ python3 script.py request_3.bin

Request type: 106

Request data:

1: "\200\200\200\200\314\200\256\201\025"

2: "\000"

3: 0x40459834dd000000

4: 0xc053f993bf000000

--------------------

Request type: 126

Request data:

--------------------

Request type: 4

Request data:

1: 1467995033798

--------------------

Request type: 129

Request data:

--------------------

Request type: 5

Request data:

1: "4a2e9bc330dae60e7b74fc85b98868ab4700802e"

--------------------

From the output, we can make several observations about each request type:

- Request type 4 seems to contain a timestamp.

- Request type 5 appears to include a 40-character hex string, suggesting a unique identifier or token.

- Request type 106 is particularly interesting - it contains fields that resemble coordinates, indicating potential relation to location tracking.

- Request types 126 and 129 are sent without additional data, which could mean they’re used as acknowledgments or status checks.

To further understand each request type, let’s examine the raw response to this request container:

1: 1

2: 1764153216922026362

6 {

1: 6

2 {

1: 1

}

}

100 {

1 {

1: -8520171482234486784

2: 1467995224486

3 {

1: "2aa8d7162e694e109cf21ae4adeb611c.16"

2: 1467972940648

3: 0x40459b2b6766bd15

4: 0xc053fae801ff9560

5: 3

6: 17

8: 1

10: 4102

}

3 {

1: "db7fbb3ce8c84f70bed1100a2db2aec3.16"

2: 1467338329663

3: 0x40459b2b67663b91

4: 0xc053fae85bffac5c

8: 1

9: 1

14: 1467989836915

}

4 {

2: 0x40459b2b67663bfc

3: 0xc053fae85bffac8f

}

4 {

2: 0x40459b2b6766bddc

3: 0xc053fae801ff9528

}

// ...

}

2: 1

}

100 {

1: 1

}

100 {

1: 1

2 {

1: 1467995033798

2: 1467995033798

}

}

100 {

1: 1

}

100 {

2: "4a2e9bc333dae60e7b74fc85b98868ab4700802e"

}

The same identifier that was sent in the 3rd field of the request container is present in the second field of the response container, confirming our suspicion that it acts as the request container identifier.

Given the structure of the request-response pattern, we expect the response container to contain a list of messages matching the number of requests sent. Indeed, this is confirmed by observing that field 100 in the response container repeats exactly 5 times, corresponding to the 5 requests. We’re now ready to define a ResponseContainer.proto:

syntax = "proto3";

message ResponseContainer {

int32 always_1 = 1;

int64 request_id = 2;

bytes message_six = 6;

repeated bytes responses = 100;

}

The repeated field 100 doesn’t seem to contain the request type corresponding to the response data. We thus have to assume that the order of responses matches the order of requests. Let’s refine our script to parse each response:

import subprocess

from sys import argv

from RequestContainer_pb2 import RequestContainer

from ResponseContainer_pb2 import ResponseContainer

def analyze_request_response_containers(request_file_name: str, response_file_name: str):

with open(request_file_name, "rb") as request:

request_container = request.read()

request_container_pb = RequestContainer.FromString(request_container)

with open(response_file_name, "rb") as response:

response_container = response.read()

response_container_pb = ResponseContainer.FromString(response_container)

for i, request in enumerate(request_container_pb.requests):

print(f"Request type: {request.request_type}")

decoded_request = subprocess.run(['protoc.exe', '--decode_raw'], input=request.additional_data, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE).stdout

print(f"Request data: {decoded_request.decode('utf-8')}")

response = response_container_pb.responses[i]

decoded_response = subprocess.run(['protoc.exe', '--decode_raw'], input=response, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE).stdout

print(f"Response data:\n{decoded_response.decode('utf-8')}")

print("-"*20)

def main():

analyze_request_container(argv[1], argv[2])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

$ python3 script.py request_3.bin response_3.bin

Request type: 106

Request data:

1: "\200\200\200\200\314\200\256\201\025"

2: "\000"

3: 0x40459834dd000000

4: 0xc053f993bf000000

Response data:

1 {

1: -8520171482234486784

2: 1467995224486

3 {

1: "2aa8d7162e694e109cf21ae4adeb611c.16"

2: 1467972940648

3: 0x40459b2b6766bd15

4: 0xc053fae801ff9560

5: 3

6: 17

8: 1

10: 4102

}

3 {

1: "db7fbb3ce8c84f70bed1100a2db2aec3.16"

2: 1467338329663

3: 0x40459b2b67663b91

4: 0xc053fae85bffac5c

8: 1

9: 1

14: 1467989836915

}

4 {

2: 0x40459b2b67663bfc

3: 0xc053fae85bffac8f

}

4 {

2: 0x40459b2b6766bddc

3: 0xc053fae801ff9528

}

// ...

}

2: 1

--------------------

Request type: 126

Request data:

Response data:

1: 1

--------------------

Request type: 4

Request data:

1: 1467995033798

Response data:

1: 1

2 {

1: 1467995033798

2: 1467995033798

}

--------------------

Request type: 129

Request data:

Response data:

1: 1

--------------------

Request type: 5

Request data:

1: "4a2e9bc340dae60e7b74fc85b98868ab4700802e"

Response data:

2: "4a2e9bc340dae60e7b74fc85b98868ab4700802e"

--------------------

At this point, we can go through a similar flow for the other request-response container pairs to uncover more request types. Instead, let’s investigate further into one request type in particular: we’ll go with request type 106 since it contains the most data in its response, warranting a deeper look.

Analyzing Request Type 106

The response to request type 106 includes multiple locations (determined by longitude-longitude pairs) within two sets of repeated fields (3 and 4). Building on our earlier educated guesses, let’s attempt to define Type106Request.proto and Type106Response.proto:

syntax = "proto3";

message Type106Request {

bytes field_1 = 1;

bytes null_byte = 2;

double latitude = 3;

double longitude = 4;

}

syntax = "proto3";

message Type106Response {

Type106DataMessage data = 1;

int32 status_maybe = 2;

}

message Type106DataMessage {

int64 id_maybe = 1;

int64 timestamp_maybe = 2;

repeated LocationOneMessage location_one = 3;

repeated LocationTwoMessage location_two = 4;

}

message LocationOneMessage {

string location_identifier_maybe = 1;

int64 timestamp_maybe_2 = 2;

double latitude = 3;

double longitude = 4;

optional int32 some_num_5 = 5;

optional int32 some_num_6 = 6;

int32 some_bool_8 = 8;

optional int32 some_bool_9 = 9;

optional int32 some_num_10 = 10;

optional int64 timestamp_maybe_14 = 14;

}

message LocationTwoMessage {

double latitude = 2;

double longitude = 3;

}

We’ll enhance our script to handle parsing request types we defined using their .proto files instead of raw decode:

import subprocess

from sysv import argv

from RequestContainer_pb2 import RequestContainer, RequestType

from ResponseContainer_pb2 import ResponseContainer

from Type106Request_pb2 import Type106Request

from Type106Response_pb2 import Type106Response

KNOWN_REQUEST_TYPE_TO_REQUEST_RESPONSE = {

RequestType.type_106: (Type106Request, Type106Response)

}

def handle_request_response(request: bytearray, response: bytearray):

if request.request_type in KNOWN_REQUEST_TYPE_TO_REQUEST_RESPONSE:

request_pb, response_pb = KNOWN_REQUEST_TYPE_TO_REQUEST_RESPONSE[request.request_type]

return request_pb.FromString(request.additional_data), response_pb.FromString(response)

else:

decoded_request = subprocess.run(['protoc.exe', '--decode_raw'], input=request.additional_data, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE).stdout

decoded_response = subprocess.run(['protoc.exe', '--decode_raw'], input=response, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE).stdout

return decoded_request, decoded_response

def analyze_request_response_containers(request_file_name: str, response_file_name: str):

with open(request_file_name, "rb") as request:

request_container = request.read()

request_container_pb = RequestContainer.FromString(request_container)

with open(response_file_name, "rb") as response:

response_container = response.read()

response_container_pb = ResponseContainer.FromString(response_container)

for i, request in enumerate(request_container_pb.requests):

response = response_container_pb.responses[i]

handle_request_response(request, response)

print(f"Request type: {request.request_type}")

print(f"Request data: {decoded_request.decode('utf-8')}")

print(f"Response data:\n{decoded_response.decode('utf-8')}")

print("-"*20)

def main():

analyze_request_container(argv[1], argv[2])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

$ python3 script.py request_3.bin response_3.bin

Request type: 106

Request data:

field_1: -8520171482234486784

null_byte: "\000"

latitude: 43.18911325931549

longitude: -79.89964270591736

Response data:

data {

id_maybe: -8520171482234486784

timestamp_maybe: 1467995224486

location_one {

location_identifier_maybe: "2aa8d7162e694e109cf21ae4adeb611c.16"

timestamp_maybe_2: 1467972940648

latitude: 43.21226208225759

longitude: -79.92041063269926

some_num_5: 3

some_num_6: 17

some_bool_8: 1

some_num_10: 4102

}

location_one {

location_identifier_maybe: "db7fbb3ce8c84f70bed1100a2db2aec3.16"

timestamp_maybe_2: 1467338329663

latitude: 43.21226208202200

longitude: -79.92043209045500

some_bool_8: 1

some_bool_9: 1

timestamp_maybe_14: 1467989836915

}

location_two {

latitude: 43.21226208202276

longitude: -79.92043209045572

}

location_two {

latitude: 43.212262082259

longitude: -79.92041063269846

}

// ...

}

status_maybe: 1

// Other request-response pairs...

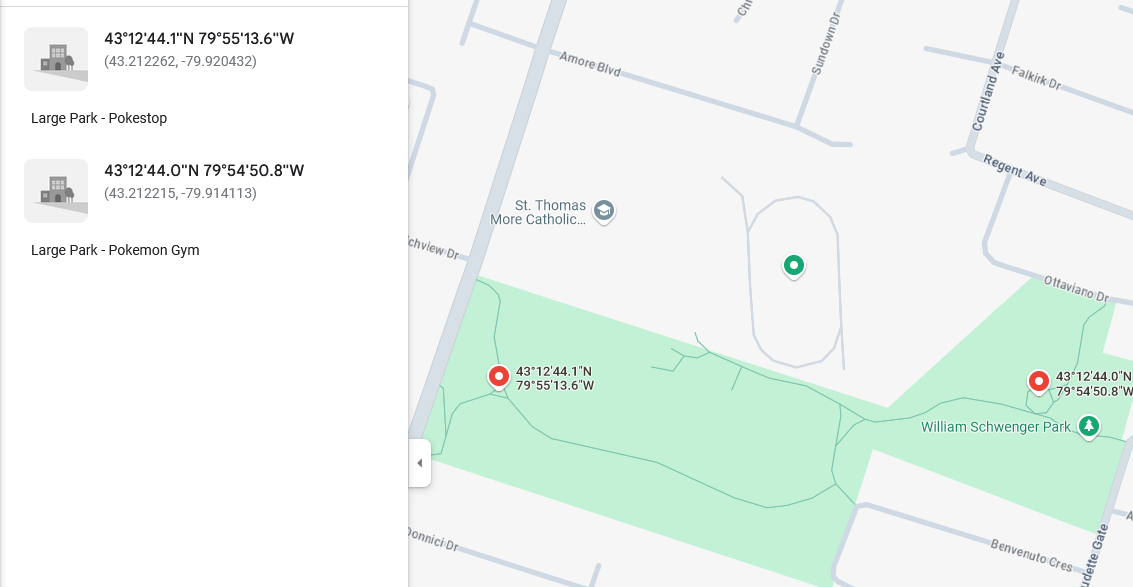

Placing the two parsed location_one on a map, we can see that LocationOneMessage marks important locations around me (important for Pokémon Go players, at least): a gym and a PokéStop!

As for LocationTwoMessage, it seems to mark coordinates around the player but lacks apparent significance…

In any case, we conclude that request type 106 is conclusively used for querying the server for important map locations.

Finding the Pokémon Location Request Type

With about 20 request types seen during Pokémon Go app’s communication, one is ought to contain the Pokémon locations utilized by the “Nearby Pokémon” feature. Diving into each request type would eventually lead us to the right request type, but as enjoyable as this detective work might be, it’s very time-consuming.

Earlier I mentioned tools capable of automatically identifying compiled .proto files within binaries. A quick look at public GitHub repositories finds relevant efforts such as POGOProtos, where individuals utilized these tools to extract and retrieve all .proto files used by Pokémon Go.

Using (a new version of) the POGOProtos repository, particularly the relevant proto file matching my version of Pokémon Go (0.31), unveils the coveted list of request types, aptly named Methods in the .proto file:

enum Method

{

METHOD_UNSET = 0;

PLAYER_UPDATE = 1;

GET_PLAYER = 2;

GET_INVENTORY = 4;

DOWNLOAD_SETTINGS = 5;

DOWNLOAD_ITEM_TEMPLATES = 6;

DOWNLOAD_REMOTE_CONFIG_VERSION = 7;

FORT_SEARCH = 101;

ENCOUNTER = 102;

CATCH_POKEMON = 103;

FORT_DETAILS = 104;

ITEM_USE = 105;

GET_MAP_OBJECTS = 106;

FORT_DEPLOY_POKEMON = 110;

FORT_RECALL_POKEMON = 111;

RELEASE_POKEMON = 112;

USE_ITEM_POTION = 113;

USE_ITEM_CAPTURE = 114;

USE_ITEM_FLEE = 115;

USE_ITEM_REVIVE = 116;

TRADE_SEARCH = 117;

TRADE_OFFER = 118;

TRADE_RESPONSE = 119;

TRADE_RESULT = 120;

GET_PLAYER_PROFILE = 121;

GET_ITEM_PACK = 122;

BUY_ITEM_PACK = 123;

BUY_GEM_PACK = 124;

EVOLVE_POKEMON = 125;

GET_HATCHED_EGGS = 126;

ENCOUNTER_TUTORIAL_COMPLETE = 127;

LEVEL_UP_REWARDS = 128;

CHECK_AWARDED_BADGES = 129;

USE_ITEM_GYM = 133;

GET_GYM_DETAILS = 134;

START_GYM_BATTLE = 135;

ATTACK_GYM = 136;

// ...

}

My gaze immediately fell on request number 106. It’s named GET_MAP_OBJECTS, a fitting name aligning perfectly with the prior black box analysis.

These server RPCs cover informational requests like player inventory or map objects, and action-oriented requests such as catching Pokémon and attacking a gym. Yet, amidst all the options, there’s no explicitly named method for fetching Pokémon locations.

Is it possible that Pokémon location data is part of the GET_MAP_OBJECTS request type? Considering Pokémon as another map object makes sense. Let’s delve into the GET_MAP_OBJECTS request type definition (during which, try to compare our black box-based definition of this request type):

message GetMapObjectsProto

{

repeated uint64 cell_id = 1;

repeated int64 since_time_ms = 2;

double player_lat = 3;

double player_lng = 4;

}

message GetMapObjectsOutProto

{

repeated ClientMapCellProto map_cell = 1;

Status status = 2;

enum Status

{

UNSET = 0;

SUCCESS = 1;

LOCATION_UNSET = 2;

}

}

The GET_MAP_OBJECTS request indeed takes a location as well as a cell_id and solicits map objects around it.

Note: Unlike our analysis concluded, it seems that the request (and thus the response) supports providing multiple map cells per query. Since we’ve only seen one cell provided in our request capture, we missed this, showing a common caveat of black box protobuf analysis.

The ClientMapCellProto message within the response most likely holds the key to understanding the different locations we’ve received in response:

message ClientMapCellProto

{

uint64 s2_cell_id = 1;

int64 as_of_time_ms = 2;

repeated PokemonFortProto fort = 3;

repeated ClientSpawnPointProto spawn_point = 4;

repeated WildPokemonProto wild_pokemon = 5;

repeated string deleted_object = 6;

bool is_truncated_list = 7;

repeated PokemonSummaryFortProto fort_summary = 8;

repeated ClientSpawnPointProto decimated_spawn_point = 9;

repeated MapPokemonProto catchable_pokemon = 10;

repeated NearbyPokemonProto nearby_pokemon = 11;

}

The ClientMapCellProto message encompasses “forts” (Pokémon Go’s internal name for gyms and PokéStops) in its third field, as I identified on my own. Pokémon spawns are present in the fourth field, which I saw but was unable to understand.

Most notably, fields 5, 10, and 11 (which didn’t appear in the response I analyzed) seem to contain info Pokémon around us. Looks like we happened to focus on the request we searched after accidentally!

Let’s use the extracted .proto file with our script to iterate over all responses we captured and look for one that contains these fields.

We find that the 5th response container includes objects from multiple map cells, two of which contain the interesting fields:

// ...

map_cell {

s2_cell_id: -8520171482234486784

as_of_time_ms: 1467995224510

fort {

fort_id: "ab4bf9634fc94dfc896f7269be1a8963.16"

last_modified_ms: 1467338329664

latitude: 35.72228384017944

longitude: 139.7710394859314

enabled: true

fort_type: CHECKPOINT

}

nearby_pokemon {

pokedex_number: 58

distance_meters: 166.94223

encounter_id: 6114343960529737261

}

}

// ...

map_cell {

s2_cell_id: -8520171482234486784

as_of_time_ms: 1467995224510

fort {

fort_id: "9feef60670b74df9871391b4b9e3ca24.16"

last_modified_ms: 1467338329663

latitude: 35.72228384017944

longitude: 139.7710394859314

enabled: true

fort_type: CHECKPOINT

}

spawn_point {

latitude: 35.72228384017531

longitude: 139.7710394859677

}

wild_pokemon {

encounter_id: 3736514205889371933

last_modified_ms: 1467995224510

latitude: 35.72228384017914

longitude: 139.7710394859256

spawn_point_id: "167fb95d5c"

pokemon {

pokemon_id: 16

}

time_till_hidden_ms: 232574

}

wild_pokemon {

encounter_id: 11920471590087242045

last_modified_ms: 1467995224510

latitude: 35.72228384013804

longitude: 139.7710394524156

spawn_point_id: "1502bffd46b"

pokemon {

pokemon_id: 23

}

time_till_hidden_ms: 204878

}

catchable_pokemon {

spawnpoint_id: "167fb95d5c"

encounter_id: 3736514205889371933

pokedex_type_id: 16

expiration_time_ms: 1467995457084

latitude: 35.72228384017914

longitude: 139.7710394859256

}

catchable_pokemon {

spawnpoint_id: "1502bffd46b"

encounter_id: 11920471590087242045

pokedex_type_id: 23

expiration_time_ms: 1467995429388

latitude: 35.72228384013804

longitude: 139.7710394524156

}

nearby_pokemon {

pokedex_number: 16

distance_meters: 66.6501617

encounter_id: 3736514205889371933

}

nearby_pokemon {

pokedex_number: 23

distance_meters: 39.9386024

encounter_id: 11920471590087242045

}

nearby_pokemon {

pokedex_number: 16

distance_meters: 187.871918

encounter_id: 16166789686219994285

}

nearby_pokemon {

pokedex_number: 16

distance_meters: 100.023682

encounter_id: 9311935069380324749

}

}

// ...

status: SUCCESS

The nearby_pokmon messages likely populate the game’s “Nearby Pokémon” paw-mark tracker, whereas the wild_pokemon and catchable_pokemon messages both contain the exact spot of the Pokémon and its type (and seem to be duplicates of each other for some reason):

catchable_pokemon {

spawnpoint_id: "1502bffd46b"

encounter_id: 11920471590087242045

pokedex_type_id: 23

expiration_time_ms: 1467995429388

latitude: 35.72228384013804

longitude: 139.7710394524156

}

And there it is, an Ekans, just one of many around me!

Evidently, the Pokémon Go app receives the exact Pokémon location data, contrary to our original assumption, rendering the initial crazy triangulation methods unnecessary. So, what’s the next step? Creating a Pokémon spawn map, naturally. With the exact location provided by the server, I’ll reach a level of precision far surpassing my initial hopes!

Building a Pokémon Scanner

With the groundwork already laid, I’m already on the verge of creating a Pokémon scanner by leveraging the following insights:

- Pokémon Go’s communication with its server is mediated through a protobuf-based RPC.

- The client uses message type 106 (

GET_MAP_OBJECTS) to fetch map details. - This message requires a cell identifier and a pair of coordinates, and its response contains the exaxct location of catchable Pokémon within the cell.

Yet, we still have two mysteries unsolved:

- What purpose do the additional fields in the request container serve?

- The nature and significance of the cell identifier in the

GET_MAP_OBJECTSrequest.

Addressing the first mystery involves the following method: we’ll replay captured requests while omitting different fields. This “least-data-method” reveals which fields are crucial at minimum to garner a response from the server:

always_2: 2

request_id_maybe: 1764153216922026362

repeated_message {

request_type_maybe: 106

additonal_data_maybe {

cell_id: -8520171482234486784

since_time_ms: 1467995033798

latitude: 28.739668607711792

longitude: 77.19470620155334

}

}

auth_maybe: "\n@\'\334W\245C\247\200\033...."

Any further omission of fields from the request container and the server replies with an error message. The server allows changing request_id_maybe as you wish, however, changing always_2 or auth_maybe is a no-go.

In fact, I noticed the validity of auth_maybe appears to be time-sensitive, and sometimes the server requires a “fresh” auth_maybe captured from the Pokémon Go app.

To understand what auth_maybe contains and its importance, we turn to the definition of RequestContainer from the extracted proto definition. It seems that RequestEnvelope is the structure name Pokémon Go app uses for this message instead:

message RequestEnvelope {

int32 status_code = 1;

uint64 request_id = 3;

repeated .POGOProtos.Networking.Requests.Request requests = 4;

double latitude = 7;

double longitude = 8;

double accuracy = 9;

AuthInfo auth_info = 10;

message AuthInfo {

string provider = 1;

JWT token = 2;

message JWT {

string contents = 1;

int32 unknown2 = 2;

}

}

.POGOProtos.Networking.Envelopes.AuthTicket auth_ticket = 11;

The proper name for auth_maybe is auth_ticket - matching our belief it is used for authentication.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the Pokémon Go server expects a valid auth_ticket to be present for requests like GET_MAP_OBJECTS to prove we’re authenticated to our account.

Through careful review of the requests sent during log-in, I figured out the process of signing into Pokémon Go with your Google account and receiving a valid, fresh auth_ticket:

- Pokémon Go sends you through Google’s OIDC-basd OAuth flow with their own OAuth app.

- You’re sent back to Pokémon Go after authenticating together with an authorization code.

- Pokémon Go exchanges the authorization code with an ID token from Google.

- Pokémon Go sends a

RequestEnvelopecontaining a single request (aGET_PLAYERrequest) to a generic RPC endpoint, containing theauth_infofield filled in withproviderequaling to"Google"and theJWTfield containing the ID token. - Pokémon Go’s server replies with an empty response. However, the

ResponseEnvelopecontains anauth_ticketin its 7th field. It also contains the exactrpcURL in its 3rd field.

message ResponseEnvelope {

StatusCode status_code = 1;

uint64 request_id = 2;

string api_url = 3;

.POGOProtos.Networking.Envelopes.AuthTicket auth_ticket = 7;

repeated bytes responses = 100;

string error = 101;

}

In our scanner, we’ll simply go through this flow - it’s not too difficult since Pokémon Go is a native app and contains the necessary client_id and client_secret to make the OAuth flow ourselves, and exchange the received ID token with an auth_ticket.

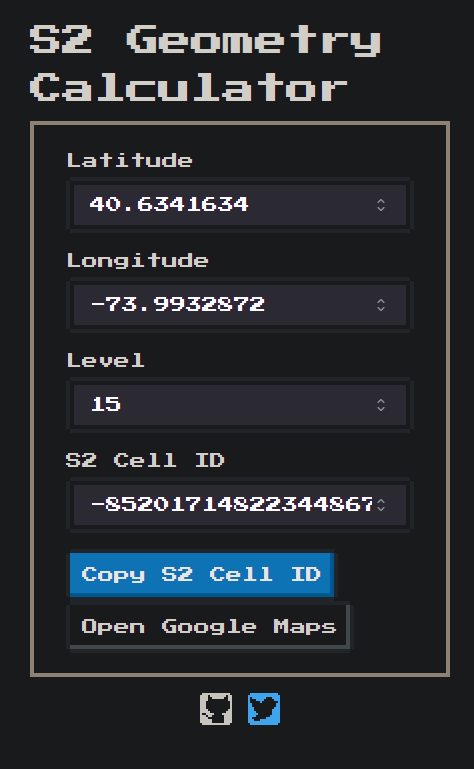

As for the second mystery - the cell identifier - we can use the extracted protos to our aid again. Notice that the relevant field for the map cell is actually called s2_cell_id. This name is derived from the s2 geometry library, which is a framework partitioning the globe into a hierarchical grid of rectangular cells.

Naturally, Pokémon Go needs to split the map around the player into logical parts it can work with, so this makes sense. How can we generate cell IDs based on coordinates? Thankfully, a very helpful person developed an open-source library that converts between coordinates and the s2 cell identifier they reside in given the appropriate level.

With all the mysteries solved, I was finally ready to create my Pokémon scanner!

Let’s start by making a function that crafts a minimal RequestEnvelope.

def create_raw_request(auth_ticket=None) -> RequestEnvelope_pb2.RequestEnvelope:

request_envelope = RequestEnvelope_pb2.RequestEnvelope()

request_envelope.status_code = 2

request_envelope.request_id = random.randint(1e18, 1e19)

if auth_ticket:

request_envelope.auth_ticket = auth_ticket

return request_envelope

We’ll then implement a function that exchanges a valid ID token of a Google account associated with a Pokémon Go account with an AuthToken and the RPC endpoint.

def get_auth_ticket_and_api_url(id_token: str) -> Tuple[ResponseEnvelope_pb2.AuthTicket, str]:

request_envelope = create_raw_request()

request = request_envelope.requests.add()

request.request_type = Method_pb2.Method.GET_MAP_OBJECTS_REQUEST

request_envelope.auth_info.provider = "google"

request_envelope.auth_info.token.contents = id_token

response = requests.post(

url="https://pgorelease.nianticlabs.com/plfe/rpc",

headers= {

"Content-Type": "application/x-www-form-urlencoded"

},

data=request_envelope.SerializeToString())

response_envelope = ResponseEnvelope_pb2.ResponseEnvelope()

response_envelope.ParseFromString(response.content)

return request_envelope.auth_ticket, request_envelope.api_url

We’ll also implement a function that dispatches a GET_MAP_OBJECTS, which translates a given pair of coordinates into s2 cell ids and fetches the relevant map objects. We’ll use the s2sphere library for s2 cell logic and ensure we only get level-15 cells.

def get_neighbors(latitude: float, longitude: float) -> List:

r = s2sphere.RegionCoverer()

r.max_level = 15

r.min_level = 15

p1 = s2sphere.LatLng.from_degrees(latitude - 0.005, longitude - 0.005)

p2 = s2sphere.LatLng.from_degrees(latitude + 0.005, longitude + 0.005)

return r.get_covering(s2sphere.LatLngRect.from_point_pair(p1, p2))

def get_map_objects(latitude:float, longitude: float, auth_ticket: ResponseEnvelope_pb2.AuthTicket, api_url: str) -> GetMapObjectsOutProto_pb2.GetMapObjectsOutProto:

request_envelope = self._create_raw_request(auth_ticket)

gmo_request_wrapper = request_envelope.requests.add()

gmo_request_wrapper.request_type = Method_pb2.Method.GET_MAP_OBJECTS

gmo_request = GetMapObjectsProto_pb2.GetMapObjectsProto()

for cell_id in get_neighbors(latitude, longitude):

gmo_request.cell_id.append(cell_id.id())

gmo_request.since_time_ms.append(0)

gmo_request.player_lat = latitude

gmo_request.player_lng = longitude

gmo_request_wrapper.message = gmo_request.SerializeToString()

requests.post(

url=api_url,

headers= {

"Content-Type": "application/x-www-form-urlencoded"

},

data=request_envelope.SerializeToString()

)

response_envelope = ResponseEnvelope_pb2.ResponseEnvelope()

response_envelope.ParseFromString(response.content)

gmo_response = GetMapObjectsOutProto_pb2.GetMapObjectsOutProto()

gmo_response.ParseFromString(response_envelope.responses[0])

return gmo_response

Concluding with a main function that receives a pair of coordinates and a valid Google ID token, and ties everything together to fetch the locations of Pokémon:

def main(latitude: float, longitude: float, id_token: str):

auth_ticket, api_url = get_auth_ticket_and_endpoint(id_token)

map_objects = get_map_objects(latitude, longitude, auth_ticket, api_url)

print(f"Received {len(map_objects.map_cell)} map cells")

for map_cell in map_objects.map_cell:

print(f"Found {len(map_cell.catchable_pokemon)} Pokémon in cell {map_cell.s2.cell_id}")

for Pokémon in map_cell.catchable_pokemon:

print(f"\tThere's a {POKEDEX[Pokémon.pokedex_type_id]} at {Pokémon.latitude}, {Pokémon.longitude}! It will be there until {time.ctime(Pokémon.expiration_time_ms / 1000.)}")

Upon running our scanner with a sample input: main(55.544044971466064, 9.340780317783356, "ey..."), we’re greeted with a detailed Pokémon location list. Time to go hunt some Pidgeys!

Received 5 map cells

Found 2 Pokémon in cell -8520171482234486784

There's a Pidgey at 55.54420221095801, 9.34093992696619! It will be there until Wed Aug 3 22:12:13 2016

There's a Pidgey at 55.54435278097566, 9.34009901287016! It will be there until Wed Aug 3 21:53:58 2016

...

Doom Approaches…

The story thus far follows my endeavors in the two weeks succeeding the launch of Pokémon Go. I had refined the scanner further to canvass a broader area than a single coordinate, searching for Pokémon across my entire hometown.

Yet, upon waking on Wednesday, August 3rd, and checking my scanner, I noticed an error - none of the GET_MAP_OBJECTS requests yielded a valid response. Instead, the server returned a nondescript error.

Confused, I reinstated the protocol capture setup and connected my phone, only to discover that isn’t working anymore. What’s going on?

Checking online, the Pokémon Go (fan) developers subreddit had already an announcement addressing this issue, alongside numerous posts by people who tried to do similar projects and encountered an identical error since midnight. A detail I overlooked that they noticed is that an update had been rolled for the Pokémon Go app overnight. Attempts to revert to an older version didn’t work, as the server actively refused connections unless the latest updated app was used.

I ventured into the subreddit’s Discord server and entered discussions about the situation. It became apparent that the Pokémon Go developers had introduced some safeguard mechanism that blocks custom implementations of the protocol.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, I was about to join on a 3-day adventure together with multiple hackers, during which we would reverse engineering and navigate through mounds of Dalvik and assembly code to overcome these protection mechanisms, all coordinated through voice calls and chat channels amidst a large audience of thousands of Pokémon Go enthusiasts eager for a breakthrough.

In the next installment of this blog, we’ll cover the work of this endeavor: the security measures unveiled, the strategies and techniques devised to circumvent them, the pivotal moment of the breakthrough during the middle of the second day, and the origins of our collective group name - Team Unknown6.

Stay tuned!